Disc brakes were hardly a new technology in 1962, as Jaguar and Dunlop had tested the concept in the crucible of motorsport as early as a decade prior at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Up to this point in the company’s history, Porsche had been using tried and true (and cheap) drum brakes, even on all but a few of its racing cars, but the company wanted to build a winning Formula 1 car for the 1962 season and needed better brakes. Instead of paying Dunlop to license the technology, Porsche set about engineering its own system, and making it lighter.

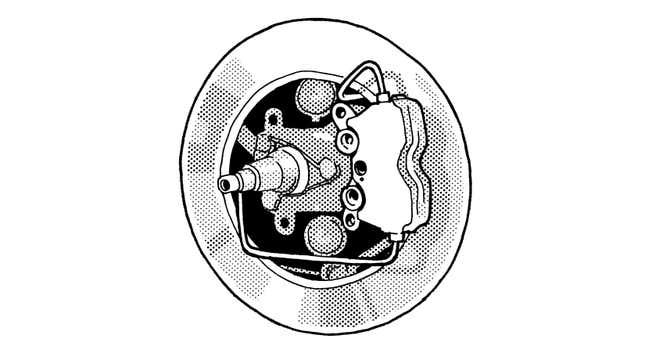

Porsche’s existing wheel hubs all used the drum brake as an integral part of the corner, mounting the wheel on its face in a “wide five” bolt pattern. Because of the company’s engineering expertise with this fashion of mounting, it decided to use the face of the drum brake as the outer mounting point for a brake disc, and pushed the caliper to the inside of the hub applying clamping force across the inner edge. The Dunlop system proved much more capable at braking from high speeds and repeatedly than drum brakes, but it came with a significant 15-pound weight penalty per corner. The new Porsche-developed “Annular” brake system was just 11 ounces heavier than its drum system, and could stop just as well as the British-designed system.

From Karl Ludvigsen’s tome about the history of Porsche “Excellence Was Expected” recounting the construction of the company’s lightweight annular brake system:

“The type 695 disc brake was tailored to gain special advantages from the characteristic Porsche wheel design, which was inherited from Volkswagen. The British disc concepts forced the use of conventional wheels with much heavier hubs instead of the light Zuffenhausen combination of a stressed brake drum married to an open-center wheel. For their own brake the Porsche designers kept the aluminum wheel carrier and gave it five spokes curving inward to lugs on the periphery of the brake disc. Thus the disc was attached to the rotating mass through its outer edge, like most aircraft disc brakes, instead of through its inner edge, the design favored by British firms.

This distinctive mounting of the Porsche disc allowed it to have the largest possible diameter (11.8 inches). This increased both the leverage and the swept area of the disc without making it overly heavy, for it consisted of only a hollow ring of iron. It was gripped from the inside by the caliper, which was made, uncommonly for those days, of aluminum.

The caliper housed two pistons behind rectangular lining pads on each side of the disc. Its pads could be removed and inserted through spaces between the disc-supporting arms. And advanced feature of the Type 695 brake was its parking brake: a simple pare of expanding shoes at each hub, which worked on the inner edge of each rear disc, effectively solving one of the most difficult problems posed by a four-wheel disc system.

MotorSport magazine spoke to Dan Gurney about his only race win in the 804 back in 2003, and he was not particularly happy with the annular brake setup on his Formula One car.

“There was a large amount of pad knock-off on bumpy surfaces so they used various means to keep the pads close to the rotors,” said Gurney. “That essentially meant you had the brakes on most of the time.”

When Porsche introduced the 356B/2000GS, informally known as the Carrera 2, in 1961, it was equipped with the nearly exactly the same braking system as the F1 car. The 2200 pound racing version of Porsche’s successful road car was equipped with a technologically advanced Fuhrmann four-cam engine making 130 horsepower. This was the first Porsche road car capable of a sub-10-second 0-60 time, and it absolutely needed better brakes to keep that extra power in check.. More from “Excellence Was Expected”:

“The cars tried by Road & Track and Auto Motor Und Sport were equipped with normal Porsche drum brakes, which did not please the German publication at all. The better acceleration and greater weight of the Carrera 2 imposed, it said, ‘the limit of conventional brakes. On our test roads they faded and pedal travel increased substantially, so that the solution of the disc brake now intrudes itself. Unfortunately the corresponding decision hasn’t yet been made at Porsche—incomprehensibly, one might say.’”

Auto Motor Und Sport editor Uli Wieselmann knew he would strike a nerve with Porsche brass. The company had been testing disc brakes (both Dunlops and internally-designed units) on its racing cars since 1958, but hadn’t quite committed to installing them on road cars. It seems automotive media’s derision for the drums and praise for the discs might have pushed Porsche over the edge in favor of the novel braking concept.

A different prototype 356 Carrera 2, fitted with the annular disc setup, was tested by Sports Car Graphic’s Bernard Cahier at the same time, and he praised the system, saying:

“The more I drove this car the more confidence I felt in these brakes. Since there was no booster they required a good amount of pressure from the brake pedal. Indeed, when the brakes were cold they needed much more pressure and did not seem to stop as quickly as they should have, while after several consecutive stops they became really good, with less pressure required on the pedal.

By 1964 all Porsche 356 models were moved to a disc brake with the introduction of the C model, though with a much more traditional hub and rotor setup, and the introduction of Porsche’s now-signature 5×130 bolt pattern. The system was really only in place for three years, but the engineering behind it was sound. Perhaps it’s time to once again embrace the annular brake rotor and integrated brake hub, especially as wheel sizes balloon. Bring back the wide-five bolt pattern Porsche, you cowards!