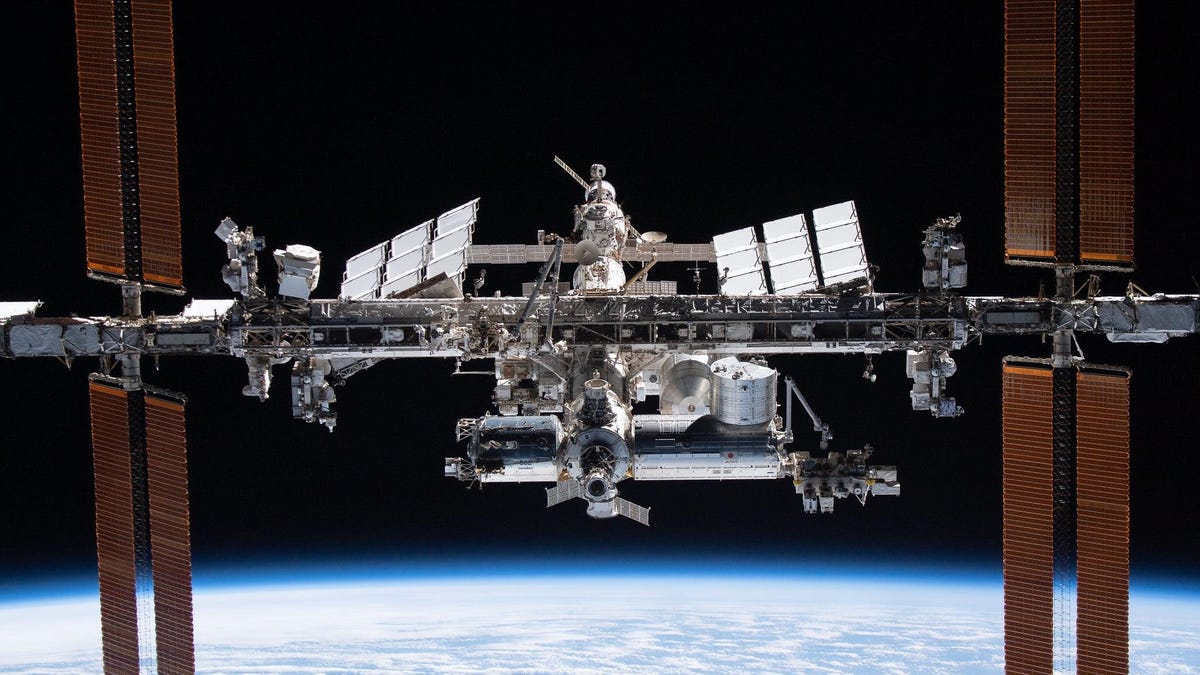

The International Space Station is literally a sinking ship. Besides being a symbol of humanity’s scientific prowess and ability to cooperate, the ISS also happens to be a 450-ton spacecraft that’s subject to gravitational forces in low Earth orbit. The ISS has lasted beyond its intended lifespan, and it requires periodic boosts to stay in orbit. NASA plans to retire it by the next decade, but it could cost nearly $1 billion to do so, as the Scientific American reports.

The destruction of the ISS is scheduled to be complete by 2031, and the agency has a few options to go about it. All of them require the ISS to return to Earth in a fiery blaze, but the most feasible option is to rely on three Russian Progress cargo vehicles that would help the ISS fall in a “deliberate, destructive descent.”

U.S.-Russia relations, however, have been strained by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Now, NASA is considering building its own deorbit vehicle but it could be costly to build such a craft. The ideal situation using NASA’s single craft is outlined by the Scientific American as follows:

All these factors combine to make the ideal process go something like this: After weeks or months of natural orbital decay that would slowly lower the ISS’s altitude, at circa 250 miles above Earth, a custom-built vehicle attached to the space station would begin a deorbit burn. The station could then descend about halfway to the planet’s surface before encountering destabilizing effects. At around 125 miles in altitude, mission controllers would adjust the ISS’s trajectory, tweaking the rocket’s burn to reshape the station’s roughly circular orbit into an ellipse, with its closest earthward point, or perigee, perhaps 90 miles above the planet. This would help minimize the amount of time that the station would spend in lower, denser levels of the atmosphere during the remainder of its descent. From that 90-mile perigee, mission control would command the rocket to fire a final time, pushing the station even farther down to fall over the South Pacific.

The other way to bring the ISS down is via an “uncontrolled deorbit,” which poses a major risk when the ISS breaks up and jettisons parts as it plummets through the atmosphere. The ISS is bigger than a football field, making it the largest object to deorbit – ever. And its orbital trajectory carries the ISS over 90 percent of the planet’s population, so an uncontrolled descent is a risky proposition that could lead to serious injury or even death.

NASA could push the ISS into higher orbit, which Scientific American refers to as the “graveyard orbit” where it would no longer be a risk, but doing so would also be expensive. And it’s likely that the station would disintegrate anyway due to its old age and sheer size, leaving behind an enormous amount of debris.

Even if Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos, agrees to assist with the vehicles needed for a controlled descent, recent events have cast a shadow on Russia’s ability to supply reliable craft for such an important mission. Russia has lately seen a number of failures that have called its once formidable space-faring capabilities into question. NASA will be looking at commercial proposals within the next few months for a custom deorbit vehicle capable of handling the mass of the ISS, but such a craft has never been needed. There are a few options but astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell says they’re not going to be cheap, according to the SA:

But if NASA wants a single deorbit vehicle with a design based on the current global space fleet, McDowell adds, it doesn’t have many options. “The things that seem obvious when you first start thinking about it—they just don’t have the oomph to do this big final burn in a short time,” McDowell says. The closest existing technology, he thinks, is the Artemis program’s European Service Module, which powered NASA’s uncrewed Orion capsule on a milestone trip around the moon last fall and is scheduled to help land humans on the lunar surface later this decade. Everything else, he says, is either far too weak or too forceful or simply unable to carry enough fuel for the task—hence NASA’s solicitation of commercial proposals for a new, custom-built deorbit vehicle.

The ISS turned 25 this year, meaning it has passed its target lifetime of 15 years by a decade; the station’s first modules reached orbit at the end of 1998. One way or another, the ISS will have to crash and burn back to Earth, and its deorbit will have to be carried out with or without Russia helping the U.S. It may just end up costing a billion to bring down the biggest object humanity has ever put into orbit.