Matt Gaetz spent the best part of Wednesday meeting with Republican senators to try and earn their support to become attorney general in a second Trump administration. Then, in the late evening, he and his entourage entered the House of Representatives.

It’s unclear why he was there. There was no reason for the former congressman — who had so recently resigned his post — to be in the House. Neither he nor anyone he was with would explain it. But, considering Gaetz is the man who broke the House, it felt a bit like watching a thief coming back to the scene of the crime.

When Trump announced his nomination of Gaetz to be the top law enforcement officer, he sent the Senate Republican conference into a miasma. Gaetz is not a popular man in Congress, among his own party or among Democrats.

Nevertheless, it looked for a while like Trump and Gaetz might get away with it.

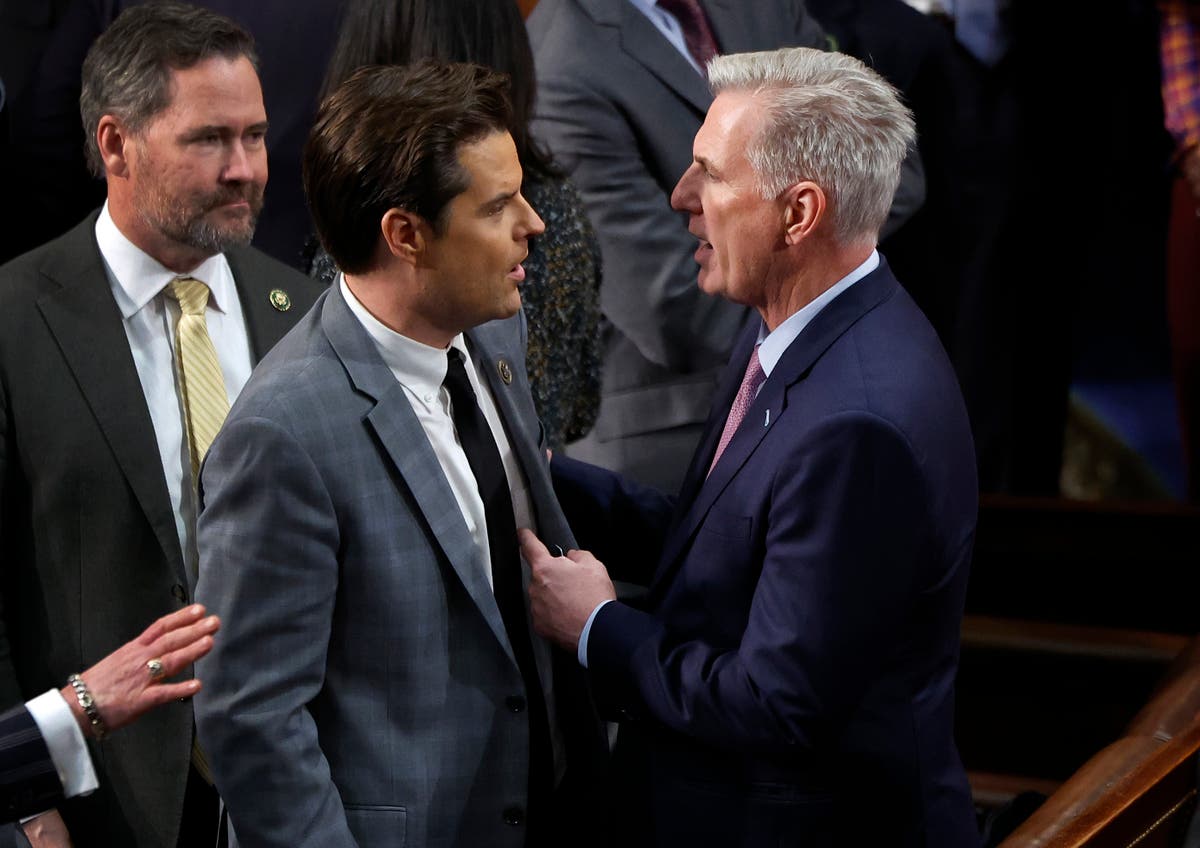

Gaetz, for his part, has proven himself to be a master of obstruction. He successfully led a charge in the first week of 2023 to block Kevin McCarthy from being speaker of the House — a charge that almost turned into a fistfight on the floor of the House. He then called his shot when McCarthy had angered just enough Republicans and every Democrat to the point that Democrats would side with someone they find as repulsive as Gaetz to take out a speaker. He mapped out a long-game strategy to install a Trump loyalist like Mike Johnson, and he succeeded.

Now, it looked like he and Trump would try to bend the Senate to their will, too.

Trump loves to make former heretics take loyalty tests. Look no further than him making JD Vance, who once compared the president-elect to Hitler, his fawning vice president. Or nominating Marco Rubio to be secretary of state. Time and time again, Trump demands that people grovel and convert. And when they do so, he hands them a reward.

What better loyalty test for the stodgiest and most institutional bodies than making a member of the lower chamber, let alone one under investigation for having sex with a teenager, attorney general?

But it turned out that it wasn’t to be. Even though Vance paraded Gaetz around the Senate and desperately tried to sell him to the Republicans there, uneasiness remained. Senators like Thom Tillis of North Carolina, who sits on the Judiciary Committee and is up for re-election, tried to shift the conversation when reporters asked about Gaetz. Nobody spoke positively about him on the record.

Then Susan Collins, the moderate Republican from Maine, told The Independent that the president-elect’s team hadn’t even bothered setting her up for a meeting with Gaetz. That either signaled a major oversight on behalf of Team Trump or a recognition nothing could make Collins vote for someone she finds as vile as Gaetz. If they weren’t bothering to chase Collins’ tie-breaking vote, it’s likely they had already given up after a bruising ordeal.

It turns out the Senate takes its “advise and consent” role seriously. And while Trump might want to put in as many loyalists who will advance his agenda, the Senate is not a body that can be brought to heel. More than any body in Washington, it does not like being told what to do.

Trump never truly understood the Senate. After the failure to repeal Obamacare, he tried to get Mitch McConnell to get rid of the filibuster, which McConnell refused. And in the depths of Covid-19, Trump threatened to adjourn the chamber to make recess appointments. But McConnell, again, refused to relent.

Even Trump’s major accomplishments in his first term in the White House were not his. McConnell and the Senate majority rammed through his judicial nominations — and it doesn’t take too much to convince Republicans to sign a major tax cut. McConnell’s decision to acquit Trump after the January 6 riot was not made out of fear of Trump, but rather out of fear other Republican senators would boot him.

And the House GOP’s attempts to conceal the Ethics Committee’s findings on Gaetz — from Johnson’s advising the committee not to release the report, to the committee chairman and the top Democrat on the committee feuding with one another — came off like the House preventing the Senate from doing its job to advise and consent.

It all finally proved too much, which is probably why Gaetz decided to pull out of the running.

Even though many of Trump’s most famous critics from the Senate — Republicans like Jeff Flake, John McCain and Mitt Romney — won’t be in the upper chamber when the president-elect returns to the White House, and many of his acolytes — like Josh Hawley, Tommy Tuberville and Ted Budd — will rubber-stamp whatever he wants, Trump learned this week that the Senate will still maintain its rules.

As for Gaetz, there is little reason to feel sorry for him. He has a litany of options. He could return to the House, boring as that may be (though he resigned from this current Congress, another one begins in January — and although he did say in his resignation letter that he doesn’t “intend” to rejoin in January, things change.) He might go for his initial goal of running for governor of Florida, which has become the MAGA Mecca in the Trump era. Or he could simply be a right-wing gadfly who makes money off his podcast, arguing that the Swamp topped him because he would fight for Trump.

But in the end, Gaetz learned that the Senate — decrepit as it may be, with its norms barely hanging on their bones — can still muster enough opposition from the rabble. It might the final bomb that Gaetz threw that simply wouldn’t detonate.