Six decades after the bullet train first whisked passengers between Tokyo and Osaka, authorities in Japan are planning to do the same for cargo, with the construction of a “conveyor belt road”.

The automated cargo transport corridor, which will connect the capital with Osaka, 320 miles (515km) away, is seen as part of the solution to soaring demand for delivery services in the world’s fourth-biggest economy.

Planners also hope the road will ease pressure on delivery drivers amid a chronic labour shortage that is affecting everything from catering and retail to haulage and public transport.

The road will also help cut carbon emissions, according to Yuri Endo, a senior official at the transport ministry who is overseeing the project.

“We need to be innovative with the way we approach roads,” Endo told the Associated Press. “The key concept of the auto flow-road is to create dedicated spaces within the road network for logistics, utilising a 24-hour automated and unmanned transportation system.”

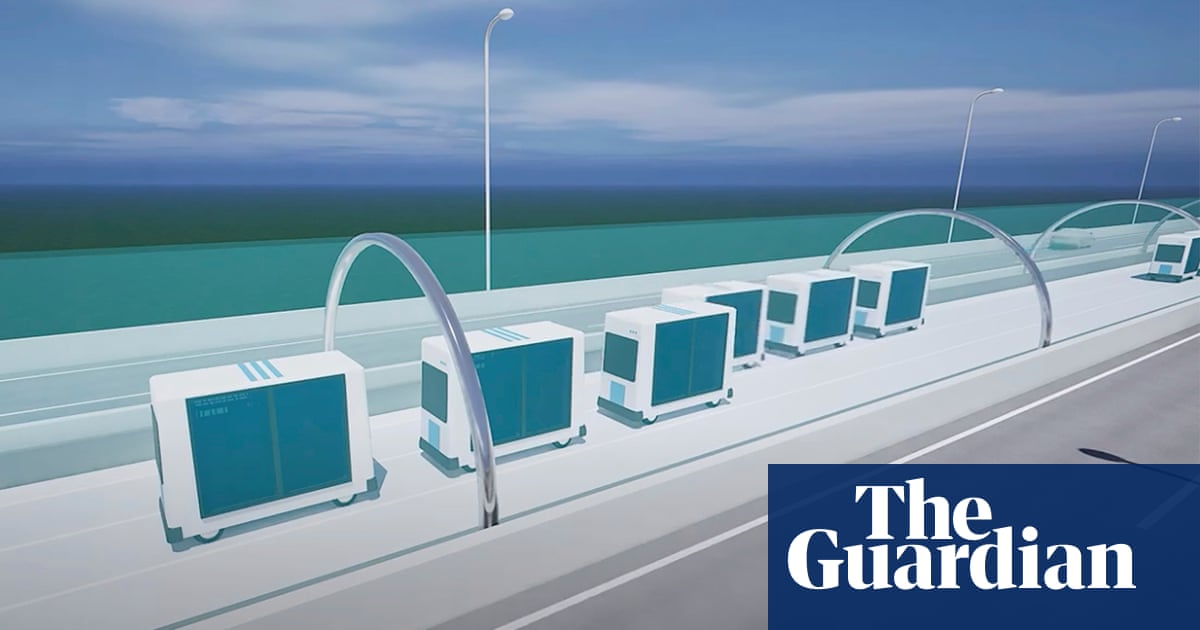

A computer-graphic video released by the government last month shows large containers on pallets – each capable of supporting up to a ton of produce – moving three abreast along an “auto flow road” in the middle of a motorway, with vehicles traveling in opposite directions on either side.

Automated forklifts will load items into the containers as part of a network that links airports, railways and ports.

Test runs are due to begin in 2027 or early 2028, with the road going into full operation in the middle of the next decade.

While no official estimates have been released, the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper said a road linking Tokyo and Osaka could cost up to ¥3.7tn [£18.6bn] given the large number of tunnels that would be needed.

If the project is successful, it could be expanded to include other parts of Japan. But humans will not be out of the picture altogether – they will still have to make door-to-door deliveries until the possible introduction of driverless vehicles.

The ministry estimates logistics motorways could do the work of 25,000 truck drivers per day, the Yomiuri said.

The shortage of truck drivers, who carry about 90% of Japan’s cargo, is expected to accelerate after the introduction this year of a law limiting their overtime in an attempt to address overwork and reduce the number of accidents.

While some have welcomed the change in a sector notorious for its long hours and difficult working conditions, the “2024 problem” will leave a gaping hole in the logistics workforce.

If the trend continues the country’s transport capacity will plunge by 34% by the end of the decade, according to government estimates.

Demand for deliveries soared in Japan during the Covid-19 pandemic, with government data showing users rising from about 40% of households to 60%.