According to a study from AAA, the average risk of severe injury for a pedestrian struck by a vehicle reaches 10 percent at an impact speed of 16 mph, 25 percent at 23 mph, 50 percent at 31 mph, 75 percent at 39 mph, and 90 percent at 46 mph. Those figures are similar when it comes to death instead of serious injury, too. Even at speeds which most drivers consider to be slow or reasonable, there are huge risks for pedestrians, and one of the most effective ways of slowing down traffic in residential areas are speed humps.

We’ve all cursed out speed bumps when we’re in a rush, but you’ve got to admit they work. The city of Los Angeles just installed speed humps on my street, which got me thinking about the different types of speed bumps, the logic behind their designs, and what makes something a speed bump versus a speed hump — yup, there’s a difference, and it’s one that car people will likely never forget.

Speed humps are typically between three and four inches in height and 12 feet in length, and are intended for use on a public roadway. A speed bump is much shorter, between one and two feet in length, but they can be twice as tall and more abrupt and infuriating. Speed bumps are typically found in parking lots or commercial driveways, but not usually on public roads, thankfully.

According to the Federal Highway Administration or FHWA, there are six different styles of speed humps, also referred to as vertical deflections: Speed humps, speed cushions, speed tables, offset speed tables, raised crosswalks, and raised intersections. These different styles of vertical deflections are generally designed as options for streets where the posted speed limit is at or below 30 mph and the 85th percentile of traffic flow before installation is traveling slower than 45 mph. Now, let’s get nerdy.

Speed Humps

Speed humps are elongated mounds in the roadway that are usually between three and four inches high, with no flat spot on top. They successfully reduce vehicle speeds to a range between 15 and 20 mph when crossing the hump, and are often strategically spaced-out to retain slower vehicle speeds over longer distances.

They’re most effective for a residential street or any street where the primary function is to provide access to abutting residential property. Speed humps are not ideal for streets that are a primary route for emergency vehicles, or a street that provides access to a hospital or other emergency services, since there’s no way to avoid these vertical deflections.

Speed humps, due to their unbroken nature, do cause delays for emergency vehicles. Fire trucks are delayed by three to five seconds, and ambulances with patients are delayed by as much as 10 seconds. For primary emergency response routes or transit routes with frequent service, it’s more logical to install speed cushions.

Speed Cushions

Speed cushions are also called speed lumps, speed slots, and speed pillows. Regardless of what you call them, they’re comparable to speed humps, though they have cutouts between raised areas to enable a large emergency vehicle to pass through without any deflection. They can also have flat tops to them, unlike speed humps.

These are meant to slow traffic flow down to 20 to 25 mph, and they’re effective on roads with speed limits of 30 mph or less. Speed cushions slow most regular traffic down without hamstringing large emergency vehicles like fire trucks and ambulances, eliminating the delays caused by traditional speed humps. This makes speed cushions viable for primary emergency vehicle routes, including streets that provide hospital or other emergency services but need regular traffic speeds to be lower.

The negatives of speed cushions include typically higher average speeds than streets with speed humps, because motorists can pass over the deflection with only one wheel on the cushion at a time. They still reduce vehicle speeds to a range of 15 to 20 mph when crossing the cushion, though a series of speed cushions is needed to maintain slower vehicle speeds. A study in the UK showed that only 45 percent of passenger car motorists aimed for the gaps when traversing a speed cushion. Speed cushions, whether single or in a series, are the most effective form of traffic calming measures other than route diversions that block access to a particular street.

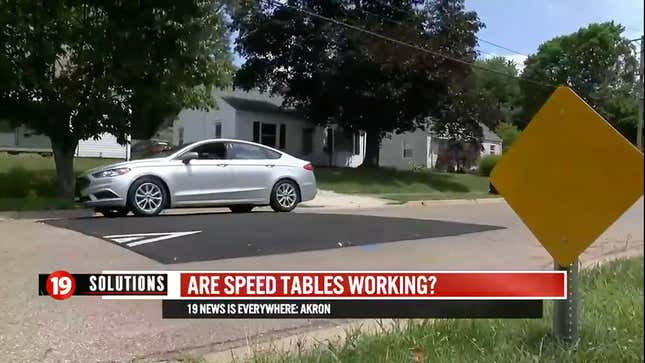

Speed Tables

Like speed humps, speed tables extend completely across a roadway, but differ from speed humps by having long flat tops that accommodate the entire wheelbase of most passenger cars. They’re designed to allow faster travel speeds than a speed hump allows. Some regions have chosen to implement speed tables on roads with 35-mph speed limits, though they are generally not appropriate for areas where the 85th percentile speeds are 45 mph or more before implementation.

Speed tables aren’t appropriate for primary emergency vehicle routes or streets that provide access to hospitals or emergency services, either, nor are they generally appropriate for bus transit routes unless the posted speed limit is 30 mph or less. A single speed table reduces 85th percentile speeds down to between 25 and 35 mph when crossing the speed table, but it’s best to place them in a series that inhibits motorists from approaching them at high speeds in either direction.

At least speed tables cause less delay for emergency vehicles than speed humps by having a less-jarring effect on long emergency vehicles like fire trucks and ambulances. Most speed tables are between three and three-and-a-half inches tall, and have overall lengths of 22 feet. Speed tables don’t usually meet the curb or side of the roadway without tapering back down to meet the flat road surface.

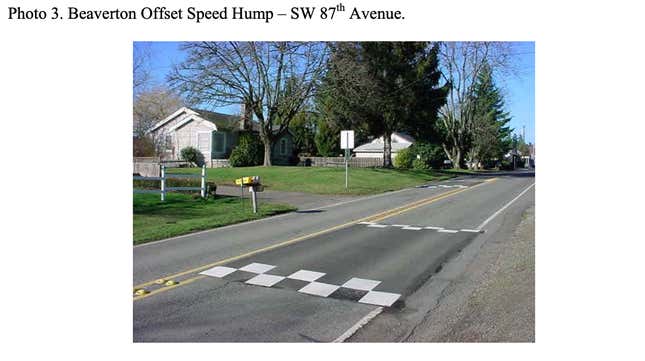

Offset Speed Tables

Where normal speed tables can delay emergency vehicles, offset speed tables minimize that delay by staggering the speed tables for each direction of traffic. They’re appropriate for two-lane, two-way streets with speed limits at or below 35 mph and where the 85th percentile of traffic flows at 45 mph or less before any vertical deflection is implemented.

Offset speed tables can be appropriate for primary emergency vehicle routes, though they aren’t ideal for bus routes or along primary access to a commercial or industrial site. They reduce the 85th percentile speeds to between 20 and 30 mph when crossing the table, but some motorists do swerve around the tables, which can be mitigated by adding small median islands.

Raised Crosswalks

These are a variation of flat-topped speed tables, but they’re constructed flush against the roadside curb to provide access for pedestrians. Raised crosswalks are between three and six inches above street level, making them taller than most speed tables, but they usually retain the same 22-foot overall travel length as speed tables, just with a crosswalk across the 10-foot plateau. They require the incorporation of all standard crosswalk design elements and need detectable warnings to alert visually impaired folks that they are entering a roadway, as they are flush with the sidewalk.

Raised crosswalks have the same speed limit recommendations as speed tables, making them acceptable for speed limits up to 35 mph and 85th-percentile traffic speeds at or below 45 mph. They are generally not appropriate for primary emergency vehicle routes, but can be appropriate for a bus transit route if speed limits are around 25 mph. These vertical deflections reduce speeds to between 20 and 30 mph when crossing the crosswalk, but still function best in a series. Pedestrian safety is improved since the vehicle speeds on the roadways are lowered, and elevating the crosswalk makes pedestrians easier for drivers to spot, and the pedestrians have a better view of oncoming traffic.

Raised Intersections

A raised intersection is precisely what it sounds like, a raised area covering an entire intersection with ramps on all approaches, or basically an entire speed table that covers an entire intersection including crosswalks. These vertical deflections are also called raised junctions, intersection humps, or plateaus, and they have similar pedestrian benefits to raised crosswalks.

Raised intersections drop 85th-percentile speeds down to between 25 and 35 mph, though they don’t make an appreciable difference in vehicle speeds as a single installation. Emergency vehicles typically cross raised intersections at slower speeds than a passenger vehicle, so they still slow emergency vehicles down more than other vertical deflections. They also likely require changes in access to subterranean utilities like sewers.

Regardless of the style of vertical deflection, speed humps help save lives by forcing drivers to slow down. Even a seemingly minute 9-mph reduction in speed from 32 mph down to 23 mph cuts the risk of killing a pedestrian by 85 percent according to this AAA study. Next time you’re rushing through a neighborhood of a busy pedestrian area, consider the statistics. And next time you cuss out a speed hump for slowing you down, consider thanking it for potentially saving lives.