A landslide and mega-tsunami in Greenland in September 2023, triggered by the climate crisis, caused the entire Earth to vibrate for nine days, a scientific investigation has found.

The seismic event was detected by earthquake sensors around the world but was so completely unprecedented that the researchers initially had no idea what had caused it. Having now solved the mystery, the scientists said it showed how global heating was already having planetary-scale impacts and that major landslides were possible in places previously believed to be stable as temperatures rapidly rose.

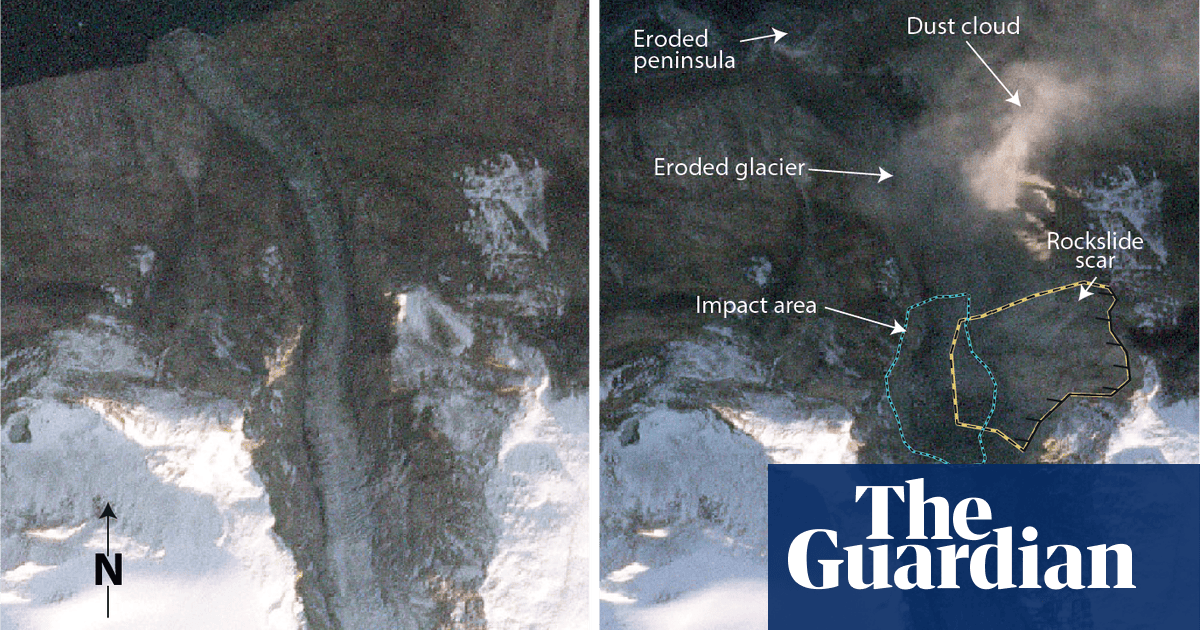

The collapse of a 1,200-metre-high mountain peak into the remote Dickson fjord happened on 16 September 2023 after the melting glacier below was no longer able to hold up the rock face. It triggered an initial wave 200 metres high and the subsequent sloshing of water back and forth in the twisty fjord sent seismic waves through the planet for more than a week.

The landslide and mega-tsunami were the first recorded in eastern Greenland. Arctic regions are being affected by the most rapid global heating, and similar though seismically smaller events have been seen in western Greenland, Alaska, Canada, Norway and Chile.

Dr Kristian Svennevig from the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, the lead author of the report, said: “When we set out on this scientific adventure, everybody was puzzled and no one had the faintest idea what caused this signal. It was far longer and simpler than earthquake signals, which usually last minutes or hours, and was labelled as a USO – an unidentified seismic object.

“It was also an extraordinary event because it is the first giant landslide and tsunami we have recorded in east Greenland at all. It definitely shows east Greenland is coming online when it comes to landslides. The waves destroyed an uninhabited Inuit site at sea level that was at least 200 years old, indicating nothing like this had happened for at least two centuries.

A large number of huts were destroyed at a research station on Ella Island, 70km (45 miles) from the landslide. The site was founded by fur hunters and explorers two centuries ago and is used by scientists and the Danish military, but was empty at the time of the tsunami.

The fjord is also on a route commonly used by tourist cruise ships and one carrying 200 people was stranded in mud in Alpefjord, close to Dickson fjord, last September. It was freed just two days before the tsunami struck, avoiding waves estimated at four to six metres.

“It was pure luck that nothing happened to any people here,” said Svennevig. “We are in uncharted waters scientifically, because we don’t really know what a tsunami does to a cruise ship.”

Dr Stephen Hicks at University College London, one of the research team leaders, said: “When I first saw the seismic signal, I was completely baffled. Never before has such a long-lasting, globally travelling seismic wave, containing only a single frequency of oscillation, been recorded.”

The signal looked completely different to multi-frequency rumbles and pings from earthquakes. It took 68 scientists from 40 institutions in 15 countries to solve the mystery by combining seismic data, field measurements, on-the-ground and satellite imagery, and high-resolution computer simulations of tsunami waves.

The analysis, published in the journal Science, estimated that 25m cubic metres of rock and ice crashed into the fjord and travelled at least 2,200 metres along it. The direction of the landslide, at 90 degrees to the length of the fjord, along with the inlet’s steep parallel walls and a 90-degree bend 10km down the line all helped to keep much of the landslide’s energy within the fjord and resonating for so long.

after newsletter promotion

The tsunami wave reduced to seven metres within a few minutes, the researchers calculated, and would have fallen to a few centimetres in the days after, when the Danish military visited and photographed the fjord. But this sloshing of a vast body of water continued to send seismic waves across the world.

Coincidentally, sensors measuring water depth had been set up by scientists in the fjord two weeks before the landslide. “That was also pure luck,” said Svennevig. “They were sailing below this glacier and mountain that they didn’t know was about to collapse.”

A key part of determining the cause of the seismic event was modelling the tsunami and comparing it against the measurements. “Our model predicted an oscillation with exactly the same period – 90 seconds – which is an amazing result, as well as the height of the tsunami, and the waves decayed in exactly the same way as seismic signals. That was the eureka moment.”

Prof Anne Mangeney, a landslide modeller at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris in France, who was part of the team, said: “This unique long-duration tsunami challenged the classical models that we previously used to simulate just a few hours of tsunami propagation – we had to go to an unprecedentedly high numerical resolution. This opens up new avenues for tsunami modelling.”

Such events will become more common as global temperatures continue to rise. “Even more profoundly, for the first time, we can quite clearly see this event, triggered by climate change, caused a global vibration beneath all of our feet, everywhere around the world,” said Mangeney. “Those vibrations travelled from Greenland to Antarctica in less than an hour. So we’ve seen an impact from climate change impacting the entire world within just an hour.”

Humans’ impact on the planet was also demonstrated recently by studies showing that the reshaping of the Earth by the mass melting of polar ice was making the length of each day longer and causing the north and south poles to shift. Other work has shown that carbon emissions are shrinking the stratosphere.