A study based on over 20 years of research into an ancient site in the Amazon rainforest has revealed evidence it was once a large-scale hub of interconnected cities that date back more than 2,500 years.

The findings were published Thursday in the journal Science and detail the researchers’ work in mapping the network of settlements, which may be the earliest example of urbanism ever documented in the Amazon.

“It was a lost valley of cities,” said Stéphen Rostain, first author of the study and a director of France’s National Center for Scientific Research. “It’s incredible.”

The team of researchers identified at least 15 distinct settlements connected by a network of roads that stretched 10 to 20 kilometres. The largest roads were found to be 10 metres at their widest.

In total, more than 6,000 earthen platforms were mapped at the Ecuadorian site, each evidence of plazas, ceremonial buildings and residences built along the road system and surrounded by expansive, terraced fields and drainage ditches.

What the research describes is a complex urban layout suggesting large-scale agriculture and a flourishing population. The hub of cities was likely home to some 10,000 farmers, though it may have been as populous as 15,000 or 30,000 at its peak, according to archaeologist Antoine Dorison, a study co-author.

The site was occupied for around 1,000 years, from roughly 500 BC to around 300 to 600 AD — a period roughly contemporaneous with the Roman Empire in Europe. The population of the Ecuadorian site is comparable to Roman-era London.

Get the latest National news.

Sent to your email, every day.

“This shows a very dense occupation and an extremely complicated society,” said University of Florida archeologist Michael Heckenberger, who was not involved in the study. “For the region, it’s really in a class of its own in terms of how early it is.”

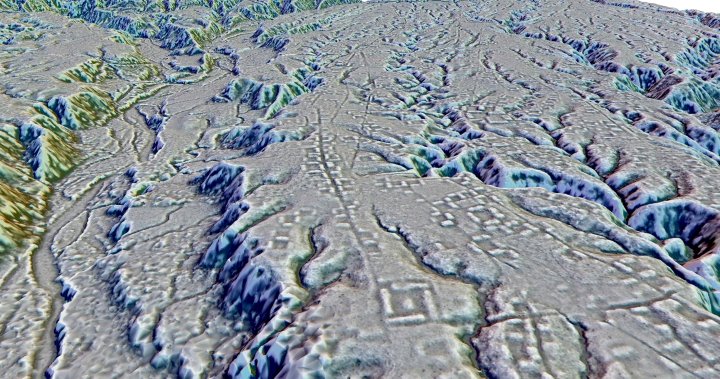

This LIDAR image provided by researchers in January 2024 shows a main street crossing an urban area, creating an axis along which complexes of rectangular platforms are arranged around low squares at the Copueno site, Upano Valley in Ecuador.

Antoine Dorison, Stéphen Rostain via AP

The site was likely inhabited by the Kilamope and later Upano peoples, but not much is known about these cultures.

Pits and hearths were discovered in some of the earthen platforms, as well as jars, grindstones and burnt seeds, the authors told the BBC. The inhabitants also likely ate maize and sweet potatoes and brewed a kind of sweet beer called “chicha.”

First author Rostain was the first archaeologist to discover the site over two decades ago, but recent improvements in light detection and ranging (LIDAR) scans have allowed scientists to pierce through the dense Amazon canopy to view these ancient sites like never before.

This LIDAR mapping shows a landscape that still bears the evidence of human hands thousands of years later, even if there isn’t much in the way of material ruins.

This LIDAR image provided by researchers in January 2024 shows complexes of rectangular platforms arranged around low squares and distributed along wide dug streets at the Kunguints site, Upano Valley in Ecuador.

Antoine Dorison, Stéphen Rostain via AP

While the Inca, for instance, built with stone, Amazonian societies typically didn’t have stone on hand to build with, so they built with mud, according to archaeologist José Iriarte, who wasn’t involved in the research.

Iriarte told the BBC that the discovery of these cities is like discovering another Mayan civilization, “but with completely different architecture, land use, ceramics.”

The authors of the study write that they hope this research helps us “revise our preconceptions of the Amazonian world” and recognize the immense complexity and diversity of people in the Amazon.

“Such a discovery is another vivid example of the underestimation of Amazonia’s twofold heritage: environmental but also cultural, and therefore Indigenous,” the paper reads.

— With files from The Associated Press

© 2024 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.