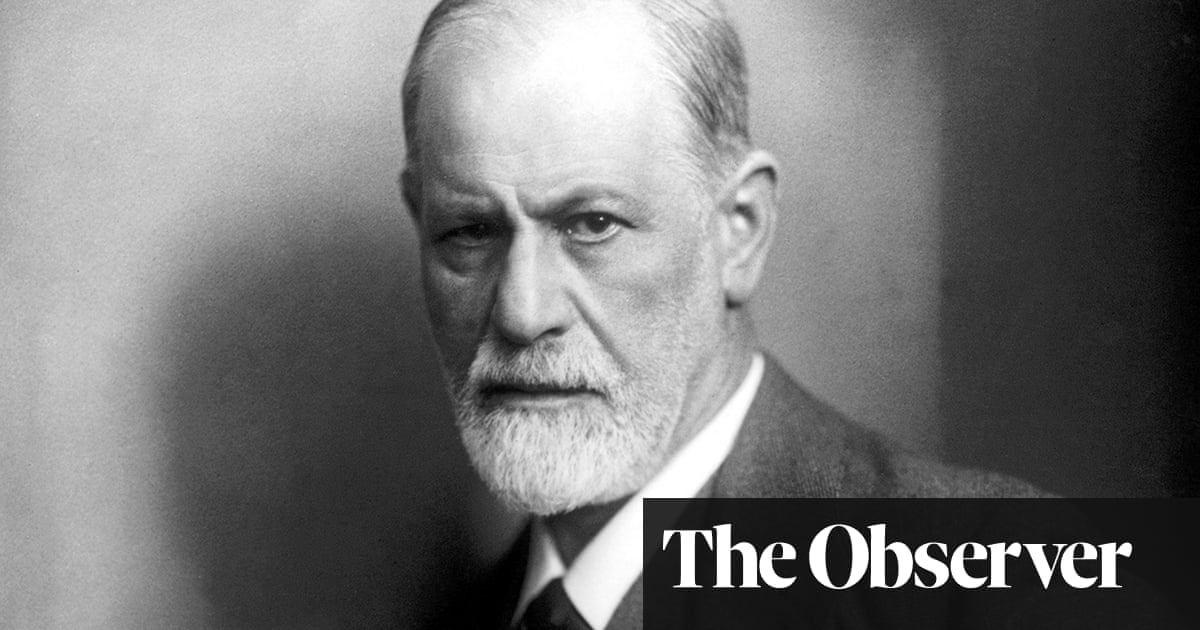

For a psychiatrist, so the joke goes, any object that crops up within a dream must represent a phallus. But it seems even Sigmund Freud did not really think all our sleeping fantasies are suppressed erotica. It was just a basic misunderstanding of the pioneering psychoanalyst’s work, according to an eminent new version of his influential theories.

A revised English edition of Freud’s key work, The Interpretation of Dreams, by scholar Mark Solms will correct several errors of translation and aim to definitively challenge the common misconception that Freud believed the erotic drive was behind much of human behaviour.

“Freud had a very broad understanding of sexuality,” said Solms, a renowned South African psychoanalyst and neuropsychologist. “For him, any activity that was pleasure seeking in its own right – anything that one does for the purposes of pleasure alone, as opposed to practical purposes – was ‘sexual’.”

In this way behaviour such as a baby sucking a dummy, or a child kicking a football, or swinging on a swing, were described by Freud as “sexual”, meaning they were pure sources of enjoyment.

“This extended the word so far beyond common usage that it led to significant misunderstanding of his theories. Late in his life, Freud acknowledged as much,” said Solms.

James Strachey’s standard English translation of Freud was printed in the 1950s and 60s. Now Solms, a German speaker who was raised in Namibia, where an older form of the language is still spoken, has removed mistakes, and is setting the word “sexual” in context. “I’ve been correcting some errors: Strachey was elderly, and his sight was poor. I’ve also changed some technical terms that are outdated now, and I’ve added some essays, lectures and other writings that weren’t in Strachey’s version,” Solms explained.

One hundred years ago Freud’s theories about sexual urges, the meaning of dreams and the struggle for emotional freedom sparked the birth of surrealism, inspiring the unsettling art of Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Giorgio de Chirico and the writings of the founder of the movement, André Breton, who wrote the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. But these artists also got Freud’s theories wrong: “None of them understood that Freud was a rather conservative gentleman and shared none of their revolutionary social inclinations,” said Solms this weekend. “His taste in art, too, was really very conservative. Freud described Dalí as a fanatic.”

While visions of our unconscious desires fuelled an explosion of disruptive art, Freud’s technical terms were wrongly used in support of the radical ideas of surrealism, Solms argues. Far from promoting anarchy or sexual liberation, Freud was a socially conservative thinker who wanted to restore order, not challenge conventions.

“The surrealist movement was explicitly predicated on Freud’s discoveries,” said Solms. “Some of them, like Dalí and de Chirico, depicted directly the inner world of the mind as it is revealed in dreams, with uncanny juxtapositions and the like, while others, like Breton, were influenced by deeper aspects of his work, and employed automatic writing and automatic drawing on the model of Freud’s free-association method. Magritte, too, understood Freud on a more intellectual level.”

Solms’s entire revised standard edition, a 24-volume epic, was commissioned by the British Psychoanalytic Society to mark the 50th anniversary of the publication of the last segment of Freud’s works, and is being released in Britain at the Freud Museum in London on 19 September, two days ahead of a special conference at University College London.

after newsletter promotion

Solms has not replaced Strachey’s earlier translation, as he sees him as “master of the English language”, who knew Freud personally. So in the updated works “subtle underlining” shows revisions and additions. Solms hopes to put the great Viennese thinker back into our conversation about dreams, although, “there are some people who would rather see Freud forgotten than retranslated. They would prefer it if he was airbrushed out of history.”

Freud originally suggested that, since sleep is biologically necessary, dreams serve the function of keeping us asleep. The hallucinatory experience of satisfaction in a dream, he argued, stops us from waking up, since “a dream that shows a wish as fulfilled is believed during sleep, it does away with the wish and makes sleep possible”.

Discoveries about the rapid eye movement period of sleep in the early 1950s prompted attacks on Freud’s wish-fulfilling theory. Instead, it was argued that REM dreams were prompted by brain stem activation, which throws up bizarre content as our organising powers are bypassed, not because our hidden desires suddenly emerge. But more recent research has revealed that we can dream both in and out of REM states, so there is no such neat explanation for the strange creativity of the sleeping mind.