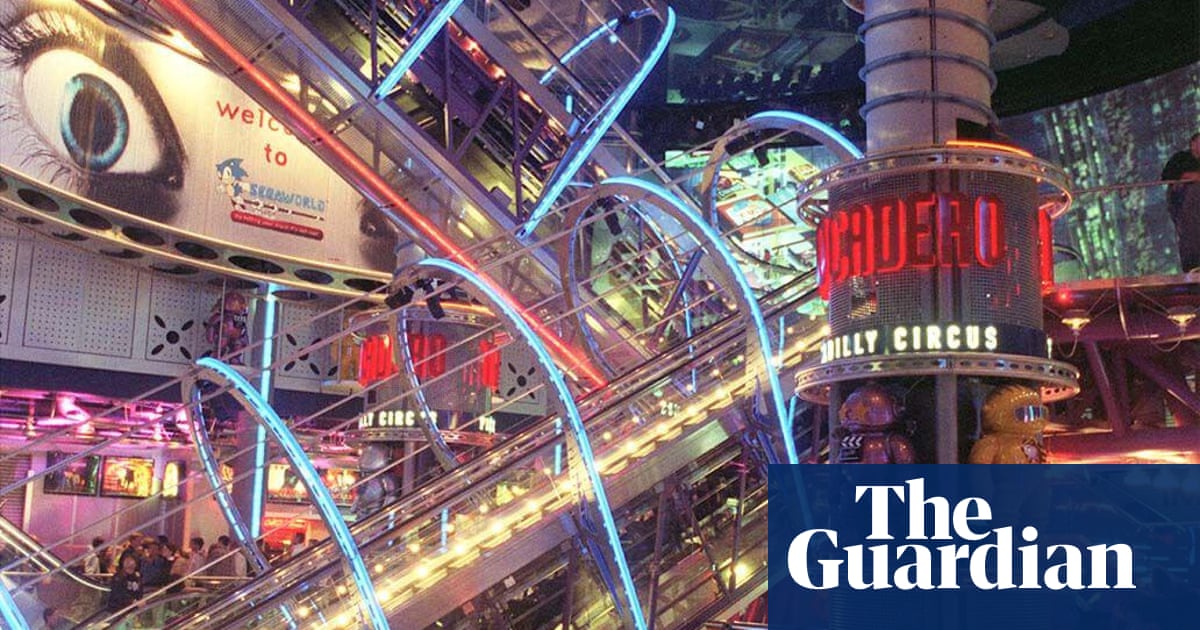

Entering central London’s Trocadero complex in the late 1990s could be an overwhelming, intoxicating experience. The vast building was then home to SegaWorld, an “indoor theme park” and arcade based on the “Joypolis” concept that the Japanese gaming giant had seen thrive in its homeland. Leaving the bustle of Coventry Street behind, visitors would pass a statue of Sonic the Hedgehog at the doors before stepping on to the famed pair of “rocket escalators”: a vision of the future delivered in brushed steel and slashes of electric blue lighting. Taking people high up into the building through a vast central open area, the escalator ride afforded a glimpse of the varied attractions that occupied each floor – the Mad Bazooka bumper car ride, the Ghost Hunt VR experience – before visitors were deposited at the top, ready to snake their way down through themed zones such as the Carnival and the Sports Arena.

All around, arcade machines chirped and sang, backed by a chorus of juddering AS-1 simulator rides, with their whining hydraulics, and the excited chatter of guests waiting in line for Sega’s VR-1 virtual reality experience, with its eight-seater pods and interactive shooter games. Intermittently the sudden mechanical wail of the Pepsi Max Drop ride would fill the air, along with the screams of its occupants. Speakers belted out the era’s biggest pop hits. Props including a full-size Harrier jump jet and carefully placed Formula 1 car occupied the gaps between the cabinets housing arcade icons such as Daytona USA and Virtua Fighter. The whole experience, Sega keenly asserted in promotional videos, was “the ultimate in futuractive entertainment”.

But this excitement and spectacle was not new to the Trocadero: it had been a place of diverse attractions for more than 200 years. After humble beginnings housing half-a-dozen simple cottages, the land was redevelopment in 1774 and variously hosted tennis courts, circuses, restaurants, billiard halls, dance performances and, for a time after the 1950s, a thriving sex trade. In 1878 it was rebranded as the Royal Trocadero Music Hall, taking its name from the Trocadéro Palace in Paris. It then became a theatre, before J Lyons & Co took over in 1896 and reopened the building as the Trocadero Restaurant, offering dances, performances, parties and Edwardian-style dining until 1965.

In 1984 the building was gutted again, before the £45m, 400,000 sq ft complex was reinvented as Britain’s largest indoor entertainment centre, containing the Guinness Book of Records exhibition, shops, and a multiplex cinema. In 1990 came an amusement arcade named Funland, offering a vast array of the latest coin-ops in a dimly lit section of the first floor. Over the next few years it would become the centre of arcade culture in the UK, housing games such as Super Street Fighter 2 Turbo, Mortal Kombat and Virtua Fighter 2 before most other coin-op palaces.

“Funland was a special place,” remembers Gabino Stergides, CEO of veteran amusements outfit Electrocoin and current Funland chief entertainment officer. “As our family had been in the amusement business for a long time, we were well connected, so we were getting all the latest import arcade games from Japan. There was never a game that didn’t go to Funland first. Funland was everybody’s barometer for which games were popular and would do well.”

The building saw an array of futuristic entertainment experiences come and go through the early 1990s. The laser gun game Quasar was there, as was Lazer Bowl, a neon-clad bowling alley that featured in an early episode of Peep Show. Trocadero was also the longest-serving venue for the Alien War experience, a “total reality” attraction based on the Aliens movie and opened by Sigourney Weaver herself in 1993. Attendees were guided through an infested facility by actors playing space marines, in an experience that anticipated the game-informed immersive theatre by companies such as Punchdrunk.

However, in September 1996 Sega arrived, taking over six floors of the Trocadero with seven theme park-syle installations. The various rides would take you to outer space, the Earth’s core or the depths of the ocean. And then there were arcade games: more than 400 of them, including eight-player linked Daytona USA and Manx TT Super Bike cabinets, often accompanied by a SegaWorld employee providing live commentary. There was Virtua Cop, Fighting Vipers, House of the Dead, the bobsleigh sim Power Sled and the super-rare Sega Net Merc VR machine. In the Autumn of 1996 it hosted the Virtua Fighter 3 Japan vs England tournament, for which Sega flew over the best Japanese players.

But it wasn’t just the games that instilled the arcades of the Trocadero in so many cherished memories. It was the building’s location, and the mix of people and cultures it consequently attracted. “The Trocadero was in the centre of things in so many ways, and that’s what made it so special,” remembers Paul Williams, CEO of Sega Amusements International, who was the managing director of SegaWorld from 1997 until its closure. “There was nowhere else like it in the UK, or even Europe; a place where so much was going on. You’d see people coming up out of Piccadilly tube station and then through the doors of SegaWorld, going up that big escalator. It was like going from normality into a spaceship. That was the idea, really. That escalator was like a portal to a new world. People had wonder in their eyes. I think that’s why so many people have such strong memories of the place.”

The Trocadero was also a place where an astounding array of subcultural groups hung out and postured; a spot for teenagers not old enough for the city’s nightlife, and an assembly point for twentysomethings getting ready to disappear into the clubs and bars of Soho. Street dance crews would perform in the tangled tunnels beneath the building, while music fans slipped in to take refuge and examine their purchases from the nearby Tower Records, which is still remembered as one of the capital’s greatest record stores.

“In a way, the Troc in the 90s was the internet before the internet,” says Toby Nanakhorn, a longstanding arcade devotee who previously fronted Las Vegas Arcade Soho and is now social media manager for London arcades Freeplay City and Funland London. “Today you can be into anything but back then, it was hard to find your people if what you liked was a bit weird. Also, if you weren’t into going out drinking and clubbing, there wasn’t much else. But there was the Troc. Us serious arcade players would go to all kinds of other London arcades, but those places were more focused on the games. The Troc offered something different. You could hang out and meet people from all over the world. All these different subcultures from outside the mainstream would mix up there. You could pretty much always go there and find people. You could be yourself. That was the appeal.”

after newsletter promotion

Ryan King, a fighting game community member and regular at London arcades, who now works for Sega, agrees that the Trocadero was a vital meeting point. “We had other arcades that were important to fighting games, smaller places like Casino up near Goodge Street,” he says. “But because of where the Troc was, that place was different – it just brought in so many more people and players passing through from all over the world. So it was important to the growth of the fighting game community. You could find something to take from it whatever your experience or ability. Maybe you’d go home the best Ken [from Street Fighter] of the day. Maybe you’d even get to say you took a round off a famous player like Ryan Hart. Or you’d get to learn from this wide range of fighting game players.”

To an extent, then, the Trocadero’s various arcades simply extended the site’s long legacy as a place that mixed up amusement and culture to the delight of passing crowds. But by the late 1990s, the arcade business was beginning its long decline. Sega exited in 1999, having failed to find a commercial model that was sustainable and popular with visitors. The rides were overcrowded and often broke down, the entry fee was expensive. Sega would ultimately hand the keys back to Funland, which remained in place at the Troc – as it is affectionately known in the arcade community to this day – until 2011. After that, a dwindling scattering of arcade cabinets could be found in the increasingly empty halls. Finally the space was shuttered in late February 2014. The building is now the 728-room Zedwell Piccadilly hotel.

Arguably, the legacy of the Troc lives on in the Brunswick shopping centre near London’s Russell Square. That is now the site of Funland, with Stergides at the reins. “It’s different from what we had at the Trocadero, but it’s a place for all kinds of people, like the Troc,” he explains. “We took over a River Island store so you’ve got retail lighting, and it’s a bright, pleasant space for families. But we still have real arcade players visiting, and we’re hosting things like pinball tournaments. So yes, in a new way that suits today, I feel like the Trocadero lives on.”

Funland’s new guise presents a compelling model. Ultimately, though, the arcade experience unique to the Troc has likely had its day. While SegaWorld and the original Funland once offered a beguiling prelude to the internet, that same force made them less relevant. Certainly the expanding technological muscle of home consoles made trips to arcades less appealing. And as online access became commonplace, we could all find our people without needing to visit central London. Niche geek cultures went mainstream, and posturing moved from reality to social media.

“The amount of kudos we used to get every day at the Trocadero was unreal,” Nanakhorn concludes. “Walking in, getting on the machine, and then having rows of people clapping – actually clapping you in public. That doesn’t happen in many places. And it felt a lot better than getting 50,000 Instagram likes.”