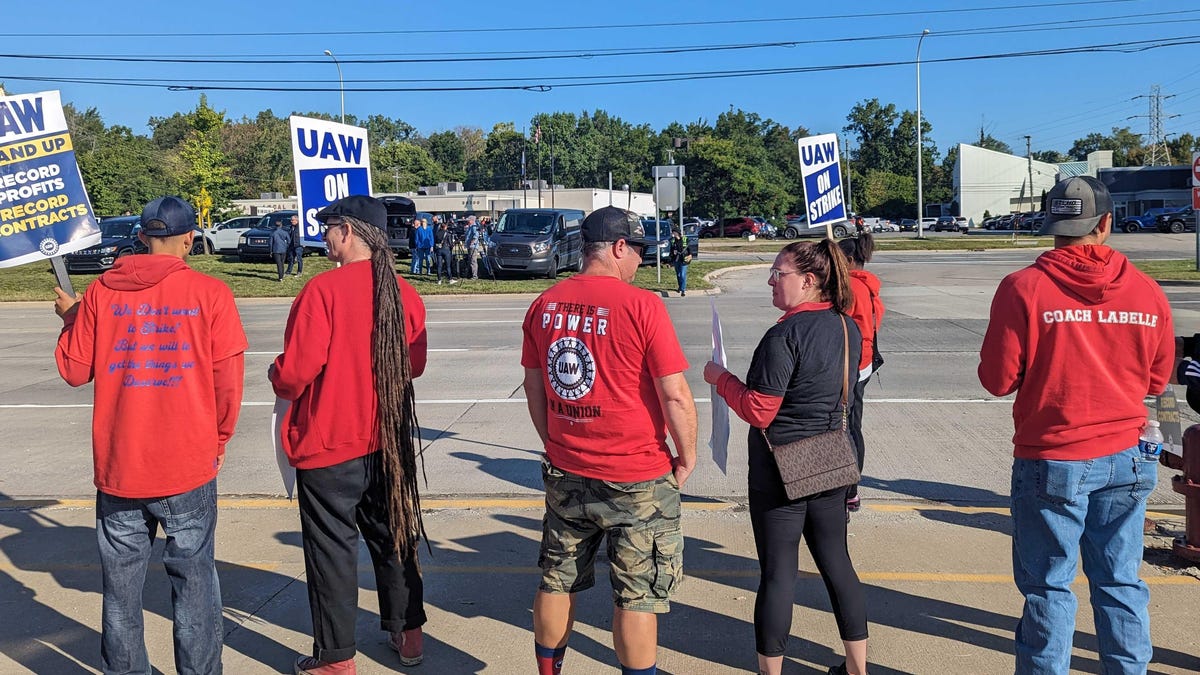

Around 13,000 UAW members went on strike against all of the Big Three automakers Friday, shutting down three plants in the Midwest. One of the first plants to go down is Ford Assembly in Wayne, Michigan, where Jalopnik spoke to strikers about their hopes for their historic collective action.

Located in a small town about 45 minutes outside of Detroit, Wayne features a large auto plant, a waste disposal dump, and a CSX train depot. Auto workers gathered on a perfect early autumn day along the busy eight-lane strode of Michigan Avenue. They cheered every driver sending them good vibes via honks, especially after a large, lifted F-250 resplendent in UAW flags bleated out for nearly a quarter of a mile as it drove by the plant.

Here in Wayne, workers build two very high-demand vehicles; the Bronco and the Ranger. Those are popular models for the Blue Oval to lose out on even a day of manufacturing and could seriously impact future sales and prices. But UAW members are also looking towards the future, with an eye on the not-too-distant past.

There was a time, not too long ago, when a good manufacturing job meant you were set for life. In Michigan, especially, an auto job meant you were able to feed your family, send them to college, and retire with dignity. After decades of steep concessions however designed to keep automakers afloat during radically difficult times, members of the United Auto Workers can see that very American dream slipping through their fingers. Now that automakers are experiencing record profits, the employees of Ford Assembly say it’s time to claw back some of those steep concessions.

One striker, who only gave his name as “Faith,” is three years into the job and therefore firmly in the infamous tier one. Newer workers have to put in years on the line at very low hourly rates before they can see the pay and benefits normally associated with a UAW job. Still, even though he’s tier one, Faith’s main focus is on the retirees, or as he calls them, “legends,” like his father-in-law.

“Things are hard on all of us. It’s been a hard few years for all of us, between COVID and inflation and housing costs. My father-in-law destroyed his body for years building cars for Ford. We don’t want to go on strike, we just want to get what we deserve. Not what we want—what we deserve.”

It’s a story you hear over and over again. Working for Ford is a family affair that often stretches back through the generations. These are not workers sold an unattainable vision by an overzealous union president; they have living memories of what it was once like to score that difficult, strenuous dream gig with one of the Big Three. Kyle Bendert just reached the second tier after five years at Ford. He’s a second-generation Ford employee, with his father and grandfather working in the same factories he now works.

“My Dad has passed but my Grandpa worked for Ford for 24 years and he should be in a much better place,” Brendert said. “Right now Ford is being so disingenuous. Jim Farley says they’ll get rid of the tier system, but we want temp workers to become full-time after 90 days. Ford doesn’t want that. What else is a bunch of underpaid perpetual temp workers if not just another tier? Ford also makes it seem like we all get five weeks of vacation. Yeah, maybe if you’ve worked here for 20 years. I just reached second tier and I only get one week of vacation that I am required to use during shutdown so I can still get paid while the plant is closed. It’s just a lot of stuff like that.”

Angela Alexander is one of those long-serving Ford employees of 25 years and the daughter of a retiree. She said the degradation in what a union job used to mean for people is why she’s striking.

“When I was hired in, everyone wanted this job. You were set for life. I knew a guy who paid a friend $1,000 just to get his application in. When I got hired, I bought a house in my 20s and started a family,” Alexander said. “But then we went to the tier system and gave up cola pay. Now you’re getting younger employees who just don’t really care as much about Ford. Working for Ford is just a stop along the way for them. It’s not a lifetime dream job anymore. I love Ford. I love working here. But we need to get back some of what we gave up. I’ve used my body up for Ford. It’s hard work, building cars. I don’t mind it, some people use their bodies to work, and that’s me, but we deserve to be compensated for that sacrifice.”

A retiree on the picket line who only gave her name as “Darling” told me after 27 years on the line, there’s nothing else she can do.

“My back is wrecked, my hips are wrecked and I’ve had surgery on my shoulder twice. Building cars is a hard job, it’ll put you in the ringer and spit you out on the other side,” Darling said. “But I’m worried about my brothers and sisters in the union, cause my retirement ain’t going so far now. I’m worried about all these people breaking their backs being left with nothing while Ford gets richer and richer.”

Even as someone who grew up around auto plants and the auto worker culture, I can’t imagine these jobs will ever mean what they once did to the communities they inhabit ever again. The dream of owning a house and making one’s way in the world on a worker’s salary seems so unattainable now, but historically, that’s exactly why we have unions. It was unions that made these jobs a dream come true, not the automakers, and it’s the unions that have a chance of bringing the dream back from the dead.